The following guide is to encourage you to read all of the articles provided in your coursepack and recommended/required on-line texts. They are keyed into related exam slides so that you can organize your time and note-taking in an appropriate fashion. On-line texts are accessed through your library account, electronic resources/Art Full Text. The articles are easily found through searching on the author's name/key words in articles, and they can be downloaded to your computer for easier access. Most exist in PDF format, which allows you to view the associated images. Please let me know if you have any trouble downloading these articles.

Study Guide for Readings, Second Half, AHIS335

Chinese Ceramics (Slides 1 through 5)

Helen Langrick Lyman's "Chinese Blue and White Trade Ceramics" (in coursepack) is an extremely useful introduction to Chinese historical periods back to the Shang Dynasty (1532-1028 BCE). The essay discusses major religious and philosophical systems as well as foreign influences. Buddhism and Confucianism and their influences on ceramic forms, kiln sites and surface decoration techniques are explored clearly. This article is an invaluable introduction to Chinese ceramics as discussed in this section as it contains useful material for all Chinese slides (1 through 5)

Jessica Harrison-Hall—"Ding and other Whitewares of Northern China"—essential for slide #2

Michael Archer, "Oriental Influence on English Delftware" (coursepack) is also useful for slide 5, Ming Dynasty "Kraak" ware. It will be useful for tin glaze earthenware later in the course.

Abstracts of On-line texts and relationship to Study Slides for Chinese Ceramics:

Kevin Grealy "Three Old Kilns from the Jingdezhen Region, Jiangxi Province" (slides 4, 5)

Discusses "Long Yao" or "dragon" kiln (words mean same thing in Chinese) by examining a number still in operation in Jingdezhen. Excellent drawings, diagrams and photos of long kiln—explanation of how it works. Originated during Shang Dynasty 3000 years ago—ranges in size 25 m to over 80, all with similar cross-section 2.5 m. in height allows workmen to stand while loading kiln—catenary, or self-supporting arch. General incline about 30 degrees. Half below, half above ground—built on old kilns. Little need for chimney stack at end as entire kiln essentially chimney—stoke holes along the way. Constructed from raw clay that fires with kiln—eventually, severe reduction spalls kilns and they need to be rebuilt. Used today to fire enormous coiled and paddled pots for pickles, storage—but soon will be phased out. Fired with brushwood and split logs. Wares often fired in saggars, but inferior clay often used—shard piles littered with ruined saggars.

William Sargent, "'Send Us no more dragons': Chinese Porcelains for the Western Market."

This article is extremely useful for Slide 5, Ming Dynasty "Kraak" ware.

The writer discusses China Trade Porcelain, Chinese ceramic exports for the Western market. Topics covered include the first porcelains to reach Europe, early general market wares, the revolution in European ceramic technology, the importance of interior design on collecting Chinese export porcelain, Dehua ware, Yixing ware, special order wares, polychrome enamels, unfired clay figures, American market wares, the importance of Chinese porcelain in late 18th-century America, and collecting Chinese export porcelain in early America.

Japanese Ceramics (Slides 6 and 7)

Victor Harris, "Ash-Glazed Stonewares in Japan" (coursepack)—essential reading.

Abstracts, On-line articles on Japanese ceramics

Louise Allison Cort, "A Chinese Green Jar in Japan: Source of a New Color Aesthetic in the Momoyama Period."

Discusses Chinese jar in Freer collection—claims the colour separates Momoyama from earlier period in terms of aesthetics. Jars from southern China, Fujian province, Zhangzhou kilns, Ming Dynasty—lead silicate glaze on stoneware-- to Japan—brilliant, acidic green created by oxidation fired copper, rather than subtle green of celadons—iron, reduction fired. Color is associated with Oribe ware, and thought to be an independent Momoyama creation (1568-1615). Oribe made at Mino kilns from about 1605 on—copper green alternates with patterns based on textiles. Green also began to influence paintings and textiles—cross media boundaries. Some jars similar to Freer jar also have yellow brown glaze (iron) and manganese—similar to Tang Dynasty sancai.

Article good for discussion of Oribe ware, new interest in colour, pattern in early 17th c. Japan.

Martha Drexler Lynn, "Useful Misunderstandings Japanese Western Mingei"

Originally thought to be uniquely Japanese, Mingei endures as a vital part of Western ceramic movements. Mingei was a creation that blended Western values derived from the 19th-century British design theorists with a longing for Japanese national identity, a lacing of Buddhist practice and aesthetics derived in part from Choson-era Korean ceramics. The fact that Mingei theory persists within both the Western and Japanese ceramics worlds after almost a century attests to the power of its blended nature, achieved through cultural accretion, useful misunderstandings, and transcultural exchanges.

Article useful for understanding controversies around concept of Mingei.

Dana Micucci, "The Way of Tea Ceramics."

This article discusses the Japanese tea ceremony and Japanese tea ceramics. Increasingly attracting the attention of many on non-Japanese people who have adopted it as a life-enhancing intellectual and spiritual and spiritual pursuit, the tea ceremony is a virtual microcosm of Japanese culture, incorporating a huge array of traditional arts and crafts, ranging from architecture and garden design to calligraphy, painting, lacquer ware, bamboo and ceramics. The essence of the ceremony is perhaps best preserved in its ceramic bowls, tea caddies, water jars, flower vases, dishes, and serving bowls, the best of which are considered by experts to be among the highest expressions of an ancient Japanese ceramic tradition.

This article is extremely useful for understanding the cultural context for both slides 6 and 7.

Discusses museum's collection of folk craft including wares from Korea (Koryo and Choson Dynasty) as well as Japanese blue-and-white wares, concept of Mingei or folk wares, Soetsu Yanagi, Shoji Hamada, Author suggests move from Koryo to Choson corresponded to shift from Victoria Oyama, "Japan Folk Crafts Museum White Porcelain and Blue-and-White" Buddhism to Confucianism—wares become more severe—white rather than blue and white, scholars tools such as water droppers for ink writing become significant. Cobalt very expensive and imported, but by 15th c., local supplies discovered so blue and white become popular again. Under Confucianism, ideals of frugality and practicality valued—thus emphasis on pure white wares—simple, severe but beautiful form and glaze. Mingei—"beauty of intimacy," also sentimentality, feeling, calmness, pleasant comfort in a world beset by problems and great difficulties.

This article is useful for understanding connections between Japan and Korea, their shared aesthetic.

Morgan Pitelka, "A Raku Wastewater Container and the Problem of Monolithic Sincerity"

A consideration of a ceramic wastewater container, or kensui, made by Raku Tannyu of the Raku family of potters in Kyoto, Japan, in 1819. The piece was made during one of Raku's workshops at the Kairakuen kiln in the garden of Wakayama Castle in the former province of Kii. The apparent simplicity of the object hides a complicated biography, meaning that its "monolithic sincerity" does not do justice to the complex identities that emerge from a careful examination of its complex history. Significantly, it is a reproduction of a famous wastewater container, known as Large Sidearm, ostensibly once owned by the influential tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-91). Both Raku's container and its antecedent can and should be considered as interrelated objects that illuminate and inform early modern and contemporary tea ceremony practices alike.

This article is very useful for slides 5 and 6, understanding Japanese concepts of wabi, the tea ceremony and Japanese concepts of tradition, copying and cultural capital.

Korean Ceramics (slide 8)

Jane Portal, "Korean Celadons of the Koryo Dynasty" (in coursepack)—essential for slide 8.

See also Oyama, discussed above.

Vietnamese Ceramics (slide 9)

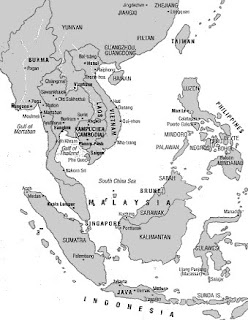

Glen Brown, "Vietnamese Blue & White Stonewares of the 14th-16th Centuries" (on-line)

The writer discusses the underglaze cobalt painted stonewares of 14th- to 16th-century Vietnam. These stonewares are among the least understood of the many historical ceramics influenced by Ming-dynasty Jingdezhen porcelains. Over the last 15 years, however, a much clearer understanding has developed of the stylistic characteristics that distinguish Vietnamese blue-and-white stonewares from similar wares made elsewhere and of how these relate to a unique cultural history and identity. Most of these Vietnamese wares were produced for export, and even the most basic pieces can have an appealing fluidity of decoration that has long been appreciated in such countries as Japan. Although rare, the most elaborate and carefully executed examples of Vietnamese blue-and-white wares compare with even the best of Chinese production from the period. The writer discusses the early trading of these stonewares.

Thai Ceramics (slide 10)

Glen Brown, "Thai Stoneware of the 14th to 16th Centuries" (on-line)

Thai stonewares occupy a prominent place during the 14th- to 16th-centuries in the complex network of Southeast Asian ceramics production and trade. By the first half of the 14th century, the Thai stoneware production industry had developed sufficiently to engage in vigorous foreign trade that would eventually carry the products of Thai kilns to places throughout Southeast Asia and as far east as the Ryukyu Islands of Japan. Made in the Sukhothai Kingdom of north central Thailand, the wares were manufactured at two principal kiln centers--Si Satchanalai and Sukhothai. An overview of Thai stoneware production from the 14th century to the 16th century is provided.

Islamic Ceramics—slides 11 and 12

Sheila Canby, "Islamic Lustreware"—course pack, essential reading.

See notes on Islamic ceramics on blogsite (2007)

Victor Cassidy, "Perpetual Glory: Islamic Ceramics of the Middle Ages" (on-line)

The article reviews the exhibition "Perpetual Glory: Medieval Islamic Ceramics from the Harvey B. Plotnick Collection," shown at the Art Institute of Chicago. Illuminating a little-known corner of ceramic history, the show featured 105 pieces, mostly bowls with a handful of architectural ceramics and a few cups, ewers, and other works. The show was part of the Silk Road Project, a year-long series of cultural events in Chicago that celebrate the network of overland and maritime trade routes that reached from the Far East across central Asia and the Iranian plateau to the Mediterranean Sea.

Mary Seyfarth, "Byzantine Glazed Ceramics."

To coincide with the 7th International Conference on Medieval Ceramics of the Mediterranean, held in October 1999, an exhibition entitled "Byzantine Glazed Ceramics The Art of Sgraffito" was organized. Held in the Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki, Greece, this unprecedented show featured functional pottery from the 11th century to post-Byzantine Greece. It demonstrated that Byzantine glazed ceramics finds its finest expression when the sgraffito line cuts through a white slip and exposes the red fabric of the clay. The show was accompanied by a handsome catalog. The writer goes on to discuss the six sgraffito processes.

This article discusses a range of ceramics related to and influenced by Islamic wares (recommended)

Slide 13, Holland, Delft, Pyramid Vase

See notes on Tin Glaze and More Notes on Tin Glaze on blogsite (2007)

See also Michael Archer, Oriental Influence on English Delftware" (course pack)

Slide 14: Italy, Deruta, Maiolica Dish:

Dora Thorton, "Maiolica Production in Renaissance Italy." (coursepack)

Slide 15: Bernard Palissy

See notes on Palissy on blogsite.

Slide 16: Medieval Jugs found in England

Beverly Nenk, "Highly Decorated Pottery in Medieval England" (coursepack)

Slide 17: England, Metropolitan Ware

David Gaimster, "Regional Decorative Traditions in English Post-Medieval Slipware" (coursepack)

Mary Wondrausch, "Flamboyance and Flair" (on-line)

The work of British ceramist Paul Young is discussed. Young has an interest in slipware, especially large medieval jugs, early pew figures, and 18th-century baking dishes, and reliquaries have perhaps been the motivation for his charming slab-built caskets. Although his primary motivation came from the early English works, it is apparent that European influences have not only crept into his patterning, but have almost engulfed these original ideas. His work reveals an unashamed joy in the slipware tradition and a skillful application of the bright colors, and one instinctively responds to the sense of tradition and history in his work.

This article discusses a contemporary artist influenced by the medieval slipware tradition.

Slide 18: Salt-Glazed stoneware vessels

See notes on German Salt Glaze on blogsite (2007)

David Gaimster, "Stoneware Production in Medieval and Early Modern Germany" (coursepack)

Slide 19: Meissen, J.J. Kaendler, Punchinello

See notes on European porcelain and German Porcelain on blogsite (2007).

Emmanuel Cooper, "European Porcelain" (coursepack)

Maureen Cassidy-Geiger, "An Italian Idyll: Meissen porcelain gifts and gift-giving" (on-line)

Chinese porcelain arriving in Venice by the 15th century sparked Italy's unparalleled appreciation for this material. The Venetian glass industry and majolica workshops responded to these princely collector's items, and the short-lived "Medici porcelain" manufactory that was set up in Florence in around 1575 was born of the experimentation that was to occupy alchemists and entrepreneurs across Europe in pursuit of a comparable ceramic industry for the next century and a half. The formula for hard-paste porcelain was ultimately discovered at the court of Saxony, and in 1710 the Royal Porcelain Manufactory began making pieces in the Albrechtsburg Castle at Meissen. Within two decades, its products were regularly being shipped abroad as royal gifts. The writer discusses the history of Meissen porcelain gift-giving.

Maureen Cassidy-Geiger, "Fabled Beasts: Augustus the Strong's Meissen Menagerie" (on-line)

Note: this article is by the same author as your required reading—you will enjoy it if you are interested in porcelain sculpture—Augustus' porcelain "menagerie" is quite spectacular.

Augustus II, "the Strong," created a porcelain menagerie in his Dutch Palace in Dresden. From about 1728, this elector of Saxony, who was king of Poland between 1697 and 1704 and from 1709 to 1733, ordered thousands of pieces of porcelain from the royal manufactory that he founded at Meissen in 1710. Almost 600 bird and animal figurines, representing both native and foreign species and made of pure porcelain in their natural scales and colors, as well as a series of imaginary beasts, were commissioned for the long gallery on the main floor of the palace, also known as the Japanese Palace. Today, several public and private collections in Europe and the United States have one or more of these figures in their collections. A number of these animal figures are pictured and described.

Slide 20: Sèvres Vases

See notes on European Porcelain French Porcelain on blogsite (2007).

Emmanuel Cooper, "European Porcelain" (coursepack)

Slides 21 and 22: Industrial Ceramics

See notes on Industrial Ceramics in Britain on blogsite (2007).

Aileen Dawson, "The Growth of the Staffordshire Ceramic Industry" (coursepack)

Kory Rogers, "Slipups: Mocha ware at the Shelburne Museum"

The vividly patterned surfaces and ornamentation of mocha ware have long attracted collectors' attention. Research into the origins of its kaleidoscopic designs has inspired in the publication of important books and articles, as well as the recent reinstallation by the Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont, of its 230 pieces of mocha ware--the biggest public collection in the world. The two year project allowed the museum staff to minutely examine its holdings, actively acquire significant pieces, and most importantly compare, contrast, and formulate conclusions regarding the creation of the remarkable surfaces of mocha ware. The writer discusses some of the museum staff's observations and findings. Items of mocha ware from the museum's collection are pictured.

This is an interesting article on a particular form of early industrial ceramics.

Garth Clark, "The Martin Brothers and their role in the art pottery movement"

The Martin brothers were a unique British collaborative of potters who stand above most in the art pottery movement. Although the brothers were social and aesthetic outcasts and were estranged from the Art and Crafts Movement, their work marks the highest point of Victorian art pottery. Each of the four brothers--Robert Wallace, Walter, Edwin, and Charles--had his own specialty in the London-based pottery. Wallace was the oldest brother and the group's driving force, and the pottery is best known today for his bird vessels. However, his talent for alienating potential friends and benefactors, along with Charles's mistrust of the commercial world, isolated the Martins and set them apart from their fellow ceramists and the Arts and Crafts Movement. The brothers were never fairly remunerated for their exceptional talent and salt-glaze sophistry, but their work has entered the pantheon of great ceramic art and grows more valued with time.

The Martin Brothers hold a great deal of interest for those attracted to sculptural and figurative ceramics. Garth Clark is an authority on their work.

Friday, October 23, 2009

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Saturday, October 17, 2009

Wedgwood "Pegasus" Vase

22. England, Wedgwood, “Pegasus” vase, 1786, jasperware, John Flaxman (younger).

22. England, Wedgwood, “Pegasus” vase, 1786, jasperware, John Flaxman (younger).The Pegasus Vase Etruria factory, Staffordshire, 1786. The body is made of pale blue jasper, and the relief decoration, handles and Pegasus of white jasper. Jasper is a type of unglazed stoneware that can be stained with colour before firing. Josiah Wedgwood I (1730-95) perfected the technique by 1775 after experiments to produce a new clay body for the making of gems. Wedgwood made multiples of the Pegasus Vase in jasper ware and in black basalt. With the sharp relief decoration set against the smooth surface, the vase is a masterpiece of the potter's art, and Wedgwood took great pride in presenting it to the British Museum in 1786. The decoration of the vase was modelled by John Flaxman junior (1755-1826). Flaxman adapted a variety of classical sources; the figures in the main scene are based on an engraving of a Greek vase of the fourth century BC, while the Medusa heads at the base of the handles are taken from an engraving of an antique sandal.D'Hancarville, author of the catalogue of Hamilton's vases, identified the central figure as the ancient Greek poet Homer. D'Hancarville shared contemporary admiration for Homer's genius and his interpretation was widely accepted.Like others, including Johann Winckelmann (1717-68), he believed that the sublime quality of Homer's poetry had transformed the visual arts from their primitive origins to the beautiful naturalism displayed here. Hamilton hoped that his collection would improve the work of artists and artisans in Britain, and this vase did prove to have a considerable influence. John Flaxman (1755-1826) copied the scene for a plaque for mantelpieces and Josiah Wedgwood used it on a jasper ware vase, known as the 'Homeric vase' or 'Pegasus Vase'. Wedgwood donated one of these vases to the British Museum in 1786 and considered it 'the finest & most perfect I have ever made'. (British Museum)

See notes on "Industry in Britain" in this blog.

Staffordshire Coffee Pot with Cover, Marbled

21. England, Staffordshire Pottery, Coffee pot and cover, marbled earthenware, 1760-70.

Agate ware is made by wedging together clays of different colours to produce a variegated slab that resembles hard stones (i.e. agate). Manganese, iron and cobalt were added to white clay to produce the colour. Table wares like this were generally lead-glazed to produce an attractive glossy surface and to prevent staining. Agate ware was produced by numerous firms in the Staffordshire area in the mid-18th c. Designs were influenced by silver pots from the 1720s. It was replaced by more fashionable creamware by the 1770s.

See notes on "Industry in Britain" in this blog.

Agate ware is made by wedging together clays of different colours to produce a variegated slab that resembles hard stones (i.e. agate). Manganese, iron and cobalt were added to white clay to produce the colour. Table wares like this were generally lead-glazed to produce an attractive glossy surface and to prevent staining. Agate ware was produced by numerous firms in the Staffordshire area in the mid-18th c. Designs were influenced by silver pots from the 1720s. It was replaced by more fashionable creamware by the 1770s.

See notes on "Industry in Britain" in this blog.

Sevres, Pair of Vases with Candle Holders

20. France, Sèvres, Pair of Vases with Candle Holders “à tête d’élephant” 1756, soft paste porcelain, by Charles-Nicolas Dodin 37.6 x 27.6 cm. (Wallace Collection, London)

Soft-paste porcelain decorated with a green ground, painted with cherubs in the manner of Boucher and gilded. The design is attributed to J-C Duplessis who worked at the factory from 1754-74; these vases may have belonged to Mme. de Pompadour. Porcelain in France develops under court patronage. No source of kaolin was discovered in France until 1768. The earliest commercial soft paste porcelain was made at Saint-Cloud in about 1693. The Chantilly factory, founded by Louis-Henry de Bourbon, prince de Condé in 1730, moved to Vincennes in 1738. At the bequest of Mme. Pompadour, it was moved to Sèvres outside Paris in 1756. Sèvres was granted exclusive privilege to make wares "in the style of Saxony" (Meissen) for 20 years and thus had no need to pursue commercial success. The factory employed hundreds of workers, some of the greatest French artists and had 7 specialist workshops. Completely at the mercy of palace power and intrigue, it produced extremely fashionable decorative objects painted with fantasy, chinoiserie-inspired scenes--potpourris, garnitures, plaques, opera glasses, ice buckets, table wares.

See notes on French porcelain in this blog.

Soft-paste porcelain decorated with a green ground, painted with cherubs in the manner of Boucher and gilded. The design is attributed to J-C Duplessis who worked at the factory from 1754-74; these vases may have belonged to Mme. de Pompadour. Porcelain in France develops under court patronage. No source of kaolin was discovered in France until 1768. The earliest commercial soft paste porcelain was made at Saint-Cloud in about 1693. The Chantilly factory, founded by Louis-Henry de Bourbon, prince de Condé in 1730, moved to Vincennes in 1738. At the bequest of Mme. Pompadour, it was moved to Sèvres outside Paris in 1756. Sèvres was granted exclusive privilege to make wares "in the style of Saxony" (Meissen) for 20 years and thus had no need to pursue commercial success. The factory employed hundreds of workers, some of the greatest French artists and had 7 specialist workshops. Completely at the mercy of palace power and intrigue, it produced extremely fashionable decorative objects painted with fantasy, chinoiserie-inspired scenes--potpourris, garnitures, plaques, opera glasses, ice buckets, table wares.

See notes on French porcelain in this blog.

Meissen, J. J. Kaendler Punchinello Figure

19. Germany, Meissen, J.J. Kaendler, figure of Punchinello, hard paste porcelain, 1740.

Kändler designed a series of porcelain of figures representing the characters from the commedia dell'arte, a popular theatre form in Europe from 1500-1700. The commedia dell'arte derives from the Italian set of stock characters and situations that date back to Roman times. Harlequin, Scaramouche, Columbine, Il Dottore, and Punchinello were well known to audiences of the time. This figure is Punchinello, the hook nosed, humpback trickster, a brutal, vindictive, and deceitful character, always at odds with authority. This character has its roots in Roman theater as a clown and would later evolve into Punch of the Punch and Judy show. The porcelain figure is glazed, and then painted and fired with overglazes and lusters. These figures were used as ornaments for centerpieces at the dining table, or as decorative objects.See notes on German hard paste porcelain in this blog.

Kändler designed a series of porcelain of figures representing the characters from the commedia dell'arte, a popular theatre form in Europe from 1500-1700. The commedia dell'arte derives from the Italian set of stock characters and situations that date back to Roman times. Harlequin, Scaramouche, Columbine, Il Dottore, and Punchinello were well known to audiences of the time. This figure is Punchinello, the hook nosed, humpback trickster, a brutal, vindictive, and deceitful character, always at odds with authority. This character has its roots in Roman theater as a clown and would later evolve into Punch of the Punch and Judy show. The porcelain figure is glazed, and then painted and fired with overglazes and lusters. These figures were used as ornaments for centerpieces at the dining table, or as decorative objects.See notes on German hard paste porcelain in this blog.

Rhineland Salt-glazed Stoneware Vessels

18. Germany, Rhineland, Salt-glazed stoneware vessels, 16th c.

Germany: Salt-Glaze-Rhineland early centre of Roman occupation, pottery traditions. Large scale production by 7th c.; kiln improvements in 9th made for tougher wares. Stoneware (steinzeug) produced between 1000-1200 CE—first in Europe (China: 500 BCE). Area favoured with wood supply, stoneware clays, river transport, population base, bronze-working traditions. Developments relate to brewing industry—introduce hops c. 1500—big upsurge in beer consumption requires hygienic, sturdy wares. Canette--in Germany, short fat pint; Schnelle: ("fast")--tall, tapering mug; Bellarmines (face modelled on neck—satirize Cardinal opposed to drinking).

See notes in blog on "Salt Glaze."

Germany: Salt-Glaze-Rhineland early centre of Roman occupation, pottery traditions. Large scale production by 7th c.; kiln improvements in 9th made for tougher wares. Stoneware (steinzeug) produced between 1000-1200 CE—first in Europe (China: 500 BCE). Area favoured with wood supply, stoneware clays, river transport, population base, bronze-working traditions. Developments relate to brewing industry—introduce hops c. 1500—big upsurge in beer consumption requires hygienic, sturdy wares. Canette--in Germany, short fat pint; Schnelle: ("fast")--tall, tapering mug; Bellarmines (face modelled on neck—satirize Cardinal opposed to drinking).

See notes in blog on "Salt Glaze."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)