The following guide is to encourage you to read all of the articles provided in your coursepack and recommended/required on-line texts. They are keyed into related exam slides so that you can organize your time and note-taking in an appropriate fashion. On-line texts are accessed through your library account, electronic resources/Art Full Text. The articles are easily found through searching on the author's name/key words in articles, and they can be downloaded to your computer for easier access. Most exist in PDF format, which allows you to view the associated images. Please let me know if you have any trouble downloading these articles.

Study Guide for Readings, Second Half, AHIS335

Chinese Ceramics (Slides 1 through 5)

Helen Langrick Lyman's "Chinese Blue and White Trade Ceramics" (in coursepack) is an extremely useful introduction to Chinese historical periods back to the Shang Dynasty (1532-1028 BCE). The essay discusses major religious and philosophical systems as well as foreign influences. Buddhism and Confucianism and their influences on ceramic forms, kiln sites and surface decoration techniques are explored clearly. This article is an invaluable introduction to Chinese ceramics as discussed in this section as it contains useful material for all Chinese slides (1 through 5)

Jessica Harrison-Hall—"Ding and other Whitewares of Northern China"—essential for slide #2

Michael Archer, "Oriental Influence on English Delftware" (coursepack) is also useful for slide 5, Ming Dynasty "Kraak" ware. It will be useful for tin glaze earthenware later in the course.

Abstracts of On-line texts and relationship to Study Slides for Chinese Ceramics:

Kevin Grealy "Three Old Kilns from the Jingdezhen Region, Jiangxi Province" (slides 4, 5)

Discusses "Long Yao" or "dragon" kiln (words mean same thing in Chinese) by examining a number still in operation in Jingdezhen. Excellent drawings, diagrams and photos of long kiln—explanation of how it works. Originated during Shang Dynasty 3000 years ago—ranges in size 25 m to over 80, all with similar cross-section 2.5 m. in height allows workmen to stand while loading kiln—catenary, or self-supporting arch. General incline about 30 degrees. Half below, half above ground—built on old kilns. Little need for chimney stack at end as entire kiln essentially chimney—stoke holes along the way. Constructed from raw clay that fires with kiln—eventually, severe reduction spalls kilns and they need to be rebuilt. Used today to fire enormous coiled and paddled pots for pickles, storage—but soon will be phased out. Fired with brushwood and split logs. Wares often fired in saggars, but inferior clay often used—shard piles littered with ruined saggars.

William Sargent, "'Send Us no more dragons': Chinese Porcelains for the Western Market."

This article is extremely useful for Slide 5, Ming Dynasty "Kraak" ware.

The writer discusses China Trade Porcelain, Chinese ceramic exports for the Western market. Topics covered include the first porcelains to reach Europe, early general market wares, the revolution in European ceramic technology, the importance of interior design on collecting Chinese export porcelain, Dehua ware, Yixing ware, special order wares, polychrome enamels, unfired clay figures, American market wares, the importance of Chinese porcelain in late 18th-century America, and collecting Chinese export porcelain in early America.

Japanese Ceramics (Slides 6 and 7)

Victor Harris, "Ash-Glazed Stonewares in Japan" (coursepack)—essential reading.

Abstracts, On-line articles on Japanese ceramics

Louise Allison Cort, "A Chinese Green Jar in Japan: Source of a New Color Aesthetic in the Momoyama Period."

Discusses Chinese jar in Freer collection—claims the colour separates Momoyama from earlier period in terms of aesthetics. Jars from southern China, Fujian province, Zhangzhou kilns, Ming Dynasty—lead silicate glaze on stoneware-- to Japan—brilliant, acidic green created by oxidation fired copper, rather than subtle green of celadons—iron, reduction fired. Color is associated with Oribe ware, and thought to be an independent Momoyama creation (1568-1615). Oribe made at Mino kilns from about 1605 on—copper green alternates with patterns based on textiles. Green also began to influence paintings and textiles—cross media boundaries. Some jars similar to Freer jar also have yellow brown glaze (iron) and manganese—similar to Tang Dynasty sancai.

Article good for discussion of Oribe ware, new interest in colour, pattern in early 17th c. Japan.

Martha Drexler Lynn, "Useful Misunderstandings Japanese Western Mingei"

Originally thought to be uniquely Japanese, Mingei endures as a vital part of Western ceramic movements. Mingei was a creation that blended Western values derived from the 19th-century British design theorists with a longing for Japanese national identity, a lacing of Buddhist practice and aesthetics derived in part from Choson-era Korean ceramics. The fact that Mingei theory persists within both the Western and Japanese ceramics worlds after almost a century attests to the power of its blended nature, achieved through cultural accretion, useful misunderstandings, and transcultural exchanges.

Article useful for understanding controversies around concept of Mingei.

Dana Micucci, "The Way of Tea Ceramics."

This article discusses the Japanese tea ceremony and Japanese tea ceramics. Increasingly attracting the attention of many on non-Japanese people who have adopted it as a life-enhancing intellectual and spiritual and spiritual pursuit, the tea ceremony is a virtual microcosm of Japanese culture, incorporating a huge array of traditional arts and crafts, ranging from architecture and garden design to calligraphy, painting, lacquer ware, bamboo and ceramics. The essence of the ceremony is perhaps best preserved in its ceramic bowls, tea caddies, water jars, flower vases, dishes, and serving bowls, the best of which are considered by experts to be among the highest expressions of an ancient Japanese ceramic tradition.

This article is extremely useful for understanding the cultural context for both slides 6 and 7.

Discusses museum's collection of folk craft including wares from Korea (Koryo and Choson Dynasty) as well as Japanese blue-and-white wares, concept of Mingei or folk wares, Soetsu Yanagi, Shoji Hamada, Author suggests move from Koryo to Choson corresponded to shift from Victoria Oyama, "Japan Folk Crafts Museum White Porcelain and Blue-and-White" Buddhism to Confucianism—wares become more severe—white rather than blue and white, scholars tools such as water droppers for ink writing become significant. Cobalt very expensive and imported, but by 15th c., local supplies discovered so blue and white become popular again. Under Confucianism, ideals of frugality and practicality valued—thus emphasis on pure white wares—simple, severe but beautiful form and glaze. Mingei—"beauty of intimacy," also sentimentality, feeling, calmness, pleasant comfort in a world beset by problems and great difficulties.

This article is useful for understanding connections between Japan and Korea, their shared aesthetic.

Morgan Pitelka, "A Raku Wastewater Container and the Problem of Monolithic Sincerity"

A consideration of a ceramic wastewater container, or kensui, made by Raku Tannyu of the Raku family of potters in Kyoto, Japan, in 1819. The piece was made during one of Raku's workshops at the Kairakuen kiln in the garden of Wakayama Castle in the former province of Kii. The apparent simplicity of the object hides a complicated biography, meaning that its "monolithic sincerity" does not do justice to the complex identities that emerge from a careful examination of its complex history. Significantly, it is a reproduction of a famous wastewater container, known as Large Sidearm, ostensibly once owned by the influential tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-91). Both Raku's container and its antecedent can and should be considered as interrelated objects that illuminate and inform early modern and contemporary tea ceremony practices alike.

This article is very useful for slides 5 and 6, understanding Japanese concepts of wabi, the tea ceremony and Japanese concepts of tradition, copying and cultural capital.

Korean Ceramics (slide 8)

Jane Portal, "Korean Celadons of the Koryo Dynasty" (in coursepack)—essential for slide 8.

See also Oyama, discussed above.

Vietnamese Ceramics (slide 9)

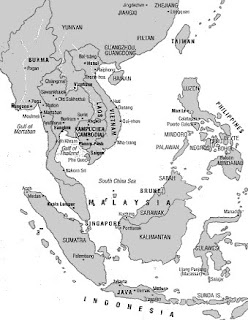

Glen Brown, "Vietnamese Blue & White Stonewares of the 14th-16th Centuries" (on-line)

The writer discusses the underglaze cobalt painted stonewares of 14th- to 16th-century Vietnam. These stonewares are among the least understood of the many historical ceramics influenced by Ming-dynasty Jingdezhen porcelains. Over the last 15 years, however, a much clearer understanding has developed of the stylistic characteristics that distinguish Vietnamese blue-and-white stonewares from similar wares made elsewhere and of how these relate to a unique cultural history and identity. Most of these Vietnamese wares were produced for export, and even the most basic pieces can have an appealing fluidity of decoration that has long been appreciated in such countries as Japan. Although rare, the most elaborate and carefully executed examples of Vietnamese blue-and-white wares compare with even the best of Chinese production from the period. The writer discusses the early trading of these stonewares.

Thai Ceramics (slide 10)

Glen Brown, "Thai Stoneware of the 14th to 16th Centuries" (on-line)

Thai stonewares occupy a prominent place during the 14th- to 16th-centuries in the complex network of Southeast Asian ceramics production and trade. By the first half of the 14th century, the Thai stoneware production industry had developed sufficiently to engage in vigorous foreign trade that would eventually carry the products of Thai kilns to places throughout Southeast Asia and as far east as the Ryukyu Islands of Japan. Made in the Sukhothai Kingdom of north central Thailand, the wares were manufactured at two principal kiln centers--Si Satchanalai and Sukhothai. An overview of Thai stoneware production from the 14th century to the 16th century is provided.

Islamic Ceramics—slides 11 and 12

Sheila Canby, "Islamic Lustreware"—course pack, essential reading.

See notes on Islamic ceramics on blogsite (2007)

Victor Cassidy, "Perpetual Glory: Islamic Ceramics of the Middle Ages" (on-line)

The article reviews the exhibition "Perpetual Glory: Medieval Islamic Ceramics from the Harvey B. Plotnick Collection," shown at the Art Institute of Chicago. Illuminating a little-known corner of ceramic history, the show featured 105 pieces, mostly bowls with a handful of architectural ceramics and a few cups, ewers, and other works. The show was part of the Silk Road Project, a year-long series of cultural events in Chicago that celebrate the network of overland and maritime trade routes that reached from the Far East across central Asia and the Iranian plateau to the Mediterranean Sea.

Mary Seyfarth, "Byzantine Glazed Ceramics."

To coincide with the 7th International Conference on Medieval Ceramics of the Mediterranean, held in October 1999, an exhibition entitled "Byzantine Glazed Ceramics The Art of Sgraffito" was organized. Held in the Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki, Greece, this unprecedented show featured functional pottery from the 11th century to post-Byzantine Greece. It demonstrated that Byzantine glazed ceramics finds its finest expression when the sgraffito line cuts through a white slip and exposes the red fabric of the clay. The show was accompanied by a handsome catalog. The writer goes on to discuss the six sgraffito processes.

This article discusses a range of ceramics related to and influenced by Islamic wares (recommended)

Slide 13, Holland, Delft, Pyramid Vase

See notes on Tin Glaze and More Notes on Tin Glaze on blogsite (2007)

See also Michael Archer, Oriental Influence on English Delftware" (course pack)

Slide 14: Italy, Deruta, Maiolica Dish:

Dora Thorton, "Maiolica Production in Renaissance Italy." (coursepack)

Slide 15: Bernard Palissy

See notes on Palissy on blogsite.

Slide 16: Medieval Jugs found in England

Beverly Nenk, "Highly Decorated Pottery in Medieval England" (coursepack)

Slide 17: England, Metropolitan Ware

David Gaimster, "Regional Decorative Traditions in English Post-Medieval Slipware" (coursepack)

Mary Wondrausch, "Flamboyance and Flair" (on-line)

The work of British ceramist Paul Young is discussed. Young has an interest in slipware, especially large medieval jugs, early pew figures, and 18th-century baking dishes, and reliquaries have perhaps been the motivation for his charming slab-built caskets. Although his primary motivation came from the early English works, it is apparent that European influences have not only crept into his patterning, but have almost engulfed these original ideas. His work reveals an unashamed joy in the slipware tradition and a skillful application of the bright colors, and one instinctively responds to the sense of tradition and history in his work.

This article discusses a contemporary artist influenced by the medieval slipware tradition.

Slide 18: Salt-Glazed stoneware vessels

See notes on German Salt Glaze on blogsite (2007)

David Gaimster, "Stoneware Production in Medieval and Early Modern Germany" (coursepack)

Slide 19: Meissen, J.J. Kaendler, Punchinello

See notes on European porcelain and German Porcelain on blogsite (2007).

Emmanuel Cooper, "European Porcelain" (coursepack)

Maureen Cassidy-Geiger, "An Italian Idyll: Meissen porcelain gifts and gift-giving" (on-line)

Chinese porcelain arriving in Venice by the 15th century sparked Italy's unparalleled appreciation for this material. The Venetian glass industry and majolica workshops responded to these princely collector's items, and the short-lived "Medici porcelain" manufactory that was set up in Florence in around 1575 was born of the experimentation that was to occupy alchemists and entrepreneurs across Europe in pursuit of a comparable ceramic industry for the next century and a half. The formula for hard-paste porcelain was ultimately discovered at the court of Saxony, and in 1710 the Royal Porcelain Manufactory began making pieces in the Albrechtsburg Castle at Meissen. Within two decades, its products were regularly being shipped abroad as royal gifts. The writer discusses the history of Meissen porcelain gift-giving.

Maureen Cassidy-Geiger, "Fabled Beasts: Augustus the Strong's Meissen Menagerie" (on-line)

Note: this article is by the same author as your required reading—you will enjoy it if you are interested in porcelain sculpture—Augustus' porcelain "menagerie" is quite spectacular.

Augustus II, "the Strong," created a porcelain menagerie in his Dutch Palace in Dresden. From about 1728, this elector of Saxony, who was king of Poland between 1697 and 1704 and from 1709 to 1733, ordered thousands of pieces of porcelain from the royal manufactory that he founded at Meissen in 1710. Almost 600 bird and animal figurines, representing both native and foreign species and made of pure porcelain in their natural scales and colors, as well as a series of imaginary beasts, were commissioned for the long gallery on the main floor of the palace, also known as the Japanese Palace. Today, several public and private collections in Europe and the United States have one or more of these figures in their collections. A number of these animal figures are pictured and described.

Slide 20: Sèvres Vases

See notes on European Porcelain French Porcelain on blogsite (2007).

Emmanuel Cooper, "European Porcelain" (coursepack)

Slides 21 and 22: Industrial Ceramics

See notes on Industrial Ceramics in Britain on blogsite (2007).

Aileen Dawson, "The Growth of the Staffordshire Ceramic Industry" (coursepack)

Kory Rogers, "Slipups: Mocha ware at the Shelburne Museum"

The vividly patterned surfaces and ornamentation of mocha ware have long attracted collectors' attention. Research into the origins of its kaleidoscopic designs has inspired in the publication of important books and articles, as well as the recent reinstallation by the Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont, of its 230 pieces of mocha ware--the biggest public collection in the world. The two year project allowed the museum staff to minutely examine its holdings, actively acquire significant pieces, and most importantly compare, contrast, and formulate conclusions regarding the creation of the remarkable surfaces of mocha ware. The writer discusses some of the museum staff's observations and findings. Items of mocha ware from the museum's collection are pictured.

This is an interesting article on a particular form of early industrial ceramics.

Garth Clark, "The Martin Brothers and their role in the art pottery movement"

The Martin brothers were a unique British collaborative of potters who stand above most in the art pottery movement. Although the brothers were social and aesthetic outcasts and were estranged from the Art and Crafts Movement, their work marks the highest point of Victorian art pottery. Each of the four brothers--Robert Wallace, Walter, Edwin, and Charles--had his own specialty in the London-based pottery. Wallace was the oldest brother and the group's driving force, and the pottery is best known today for his bird vessels. However, his talent for alienating potential friends and benefactors, along with Charles's mistrust of the commercial world, isolated the Martins and set them apart from their fellow ceramists and the Arts and Crafts Movement. The brothers were never fairly remunerated for their exceptional talent and salt-glaze sophistry, but their work has entered the pantheon of great ceramic art and grows more valued with time.

The Martin Brothers hold a great deal of interest for those attracted to sculptural and figurative ceramics. Garth Clark is an authority on their work.

Friday, October 23, 2009

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Saturday, October 17, 2009

Wedgwood "Pegasus" Vase

22. England, Wedgwood, “Pegasus” vase, 1786, jasperware, John Flaxman (younger).

22. England, Wedgwood, “Pegasus” vase, 1786, jasperware, John Flaxman (younger).The Pegasus Vase Etruria factory, Staffordshire, 1786. The body is made of pale blue jasper, and the relief decoration, handles and Pegasus of white jasper. Jasper is a type of unglazed stoneware that can be stained with colour before firing. Josiah Wedgwood I (1730-95) perfected the technique by 1775 after experiments to produce a new clay body for the making of gems. Wedgwood made multiples of the Pegasus Vase in jasper ware and in black basalt. With the sharp relief decoration set against the smooth surface, the vase is a masterpiece of the potter's art, and Wedgwood took great pride in presenting it to the British Museum in 1786. The decoration of the vase was modelled by John Flaxman junior (1755-1826). Flaxman adapted a variety of classical sources; the figures in the main scene are based on an engraving of a Greek vase of the fourth century BC, while the Medusa heads at the base of the handles are taken from an engraving of an antique sandal.D'Hancarville, author of the catalogue of Hamilton's vases, identified the central figure as the ancient Greek poet Homer. D'Hancarville shared contemporary admiration for Homer's genius and his interpretation was widely accepted.Like others, including Johann Winckelmann (1717-68), he believed that the sublime quality of Homer's poetry had transformed the visual arts from their primitive origins to the beautiful naturalism displayed here. Hamilton hoped that his collection would improve the work of artists and artisans in Britain, and this vase did prove to have a considerable influence. John Flaxman (1755-1826) copied the scene for a plaque for mantelpieces and Josiah Wedgwood used it on a jasper ware vase, known as the 'Homeric vase' or 'Pegasus Vase'. Wedgwood donated one of these vases to the British Museum in 1786 and considered it 'the finest & most perfect I have ever made'. (British Museum)

See notes on "Industry in Britain" in this blog.

Staffordshire Coffee Pot with Cover, Marbled

21. England, Staffordshire Pottery, Coffee pot and cover, marbled earthenware, 1760-70.

Agate ware is made by wedging together clays of different colours to produce a variegated slab that resembles hard stones (i.e. agate). Manganese, iron and cobalt were added to white clay to produce the colour. Table wares like this were generally lead-glazed to produce an attractive glossy surface and to prevent staining. Agate ware was produced by numerous firms in the Staffordshire area in the mid-18th c. Designs were influenced by silver pots from the 1720s. It was replaced by more fashionable creamware by the 1770s.

See notes on "Industry in Britain" in this blog.

Agate ware is made by wedging together clays of different colours to produce a variegated slab that resembles hard stones (i.e. agate). Manganese, iron and cobalt were added to white clay to produce the colour. Table wares like this were generally lead-glazed to produce an attractive glossy surface and to prevent staining. Agate ware was produced by numerous firms in the Staffordshire area in the mid-18th c. Designs were influenced by silver pots from the 1720s. It was replaced by more fashionable creamware by the 1770s.

See notes on "Industry in Britain" in this blog.

Sevres, Pair of Vases with Candle Holders

20. France, Sèvres, Pair of Vases with Candle Holders “à tête d’élephant” 1756, soft paste porcelain, by Charles-Nicolas Dodin 37.6 x 27.6 cm. (Wallace Collection, London)

Soft-paste porcelain decorated with a green ground, painted with cherubs in the manner of Boucher and gilded. The design is attributed to J-C Duplessis who worked at the factory from 1754-74; these vases may have belonged to Mme. de Pompadour. Porcelain in France develops under court patronage. No source of kaolin was discovered in France until 1768. The earliest commercial soft paste porcelain was made at Saint-Cloud in about 1693. The Chantilly factory, founded by Louis-Henry de Bourbon, prince de Condé in 1730, moved to Vincennes in 1738. At the bequest of Mme. Pompadour, it was moved to Sèvres outside Paris in 1756. Sèvres was granted exclusive privilege to make wares "in the style of Saxony" (Meissen) for 20 years and thus had no need to pursue commercial success. The factory employed hundreds of workers, some of the greatest French artists and had 7 specialist workshops. Completely at the mercy of palace power and intrigue, it produced extremely fashionable decorative objects painted with fantasy, chinoiserie-inspired scenes--potpourris, garnitures, plaques, opera glasses, ice buckets, table wares.

See notes on French porcelain in this blog.

Soft-paste porcelain decorated with a green ground, painted with cherubs in the manner of Boucher and gilded. The design is attributed to J-C Duplessis who worked at the factory from 1754-74; these vases may have belonged to Mme. de Pompadour. Porcelain in France develops under court patronage. No source of kaolin was discovered in France until 1768. The earliest commercial soft paste porcelain was made at Saint-Cloud in about 1693. The Chantilly factory, founded by Louis-Henry de Bourbon, prince de Condé in 1730, moved to Vincennes in 1738. At the bequest of Mme. Pompadour, it was moved to Sèvres outside Paris in 1756. Sèvres was granted exclusive privilege to make wares "in the style of Saxony" (Meissen) for 20 years and thus had no need to pursue commercial success. The factory employed hundreds of workers, some of the greatest French artists and had 7 specialist workshops. Completely at the mercy of palace power and intrigue, it produced extremely fashionable decorative objects painted with fantasy, chinoiserie-inspired scenes--potpourris, garnitures, plaques, opera glasses, ice buckets, table wares.

See notes on French porcelain in this blog.

Meissen, J. J. Kaendler Punchinello Figure

19. Germany, Meissen, J.J. Kaendler, figure of Punchinello, hard paste porcelain, 1740.

Kändler designed a series of porcelain of figures representing the characters from the commedia dell'arte, a popular theatre form in Europe from 1500-1700. The commedia dell'arte derives from the Italian set of stock characters and situations that date back to Roman times. Harlequin, Scaramouche, Columbine, Il Dottore, and Punchinello were well known to audiences of the time. This figure is Punchinello, the hook nosed, humpback trickster, a brutal, vindictive, and deceitful character, always at odds with authority. This character has its roots in Roman theater as a clown and would later evolve into Punch of the Punch and Judy show. The porcelain figure is glazed, and then painted and fired with overglazes and lusters. These figures were used as ornaments for centerpieces at the dining table, or as decorative objects.See notes on German hard paste porcelain in this blog.

Kändler designed a series of porcelain of figures representing the characters from the commedia dell'arte, a popular theatre form in Europe from 1500-1700. The commedia dell'arte derives from the Italian set of stock characters and situations that date back to Roman times. Harlequin, Scaramouche, Columbine, Il Dottore, and Punchinello were well known to audiences of the time. This figure is Punchinello, the hook nosed, humpback trickster, a brutal, vindictive, and deceitful character, always at odds with authority. This character has its roots in Roman theater as a clown and would later evolve into Punch of the Punch and Judy show. The porcelain figure is glazed, and then painted and fired with overglazes and lusters. These figures were used as ornaments for centerpieces at the dining table, or as decorative objects.See notes on German hard paste porcelain in this blog.

Rhineland Salt-glazed Stoneware Vessels

18. Germany, Rhineland, Salt-glazed stoneware vessels, 16th c.

Germany: Salt-Glaze-Rhineland early centre of Roman occupation, pottery traditions. Large scale production by 7th c.; kiln improvements in 9th made for tougher wares. Stoneware (steinzeug) produced between 1000-1200 CE—first in Europe (China: 500 BCE). Area favoured with wood supply, stoneware clays, river transport, population base, bronze-working traditions. Developments relate to brewing industry—introduce hops c. 1500—big upsurge in beer consumption requires hygienic, sturdy wares. Canette--in Germany, short fat pint; Schnelle: ("fast")--tall, tapering mug; Bellarmines (face modelled on neck—satirize Cardinal opposed to drinking).

See notes in blog on "Salt Glaze."

Germany: Salt-Glaze-Rhineland early centre of Roman occupation, pottery traditions. Large scale production by 7th c.; kiln improvements in 9th made for tougher wares. Stoneware (steinzeug) produced between 1000-1200 CE—first in Europe (China: 500 BCE). Area favoured with wood supply, stoneware clays, river transport, population base, bronze-working traditions. Developments relate to brewing industry—introduce hops c. 1500—big upsurge in beer consumption requires hygienic, sturdy wares. Canette--in Germany, short fat pint; Schnelle: ("fast")--tall, tapering mug; Bellarmines (face modelled on neck—satirize Cardinal opposed to drinking).

See notes in blog on "Salt Glaze."

England, Metropolitan Ware

17. England, Metropolitan ware, red earthenware trailed and feathered slip, 17th c.

The slipware industry developed in England as part of a "pan-European fashion" for decorative tablewares. Wares such as these competed with more expensive tin-glazed wares, which represented the height of fashion in middle-class homes. Tin-glaze, in turn, competed with and was influenced by blue and white Chinese porcelain imported into the region at this time. The designs were made by trailing light coloured slip onto red earthenware through a cow-horn or pottery vessel fitted with a quill or reed; the wares were then lead-glazed and once-fired, making a very economical product for the lower end of the social spectrum. A wide range of decorative motifs were employed including geometric, floral and figural designs appropriate for the urban market. One defining feature was the use of texts, a practice possibly originating in the previous century in the Rhineland area of Germany with texts added to salt-glazed stoneware. Metropolitan wares produced in Essex featured texts applied in block letters with pious aphorisms urging humility, charity or loyalty to the crown. Texts influenced by the Puritan government of the day were replaced with royalist messages after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. See David Gaimster, "Regional Decorative Traditions in English Post-Medieval Slipware," in your course text, pp 129-130.

The slipware industry developed in England as part of a "pan-European fashion" for decorative tablewares. Wares such as these competed with more expensive tin-glazed wares, which represented the height of fashion in middle-class homes. Tin-glaze, in turn, competed with and was influenced by blue and white Chinese porcelain imported into the region at this time. The designs were made by trailing light coloured slip onto red earthenware through a cow-horn or pottery vessel fitted with a quill or reed; the wares were then lead-glazed and once-fired, making a very economical product for the lower end of the social spectrum. A wide range of decorative motifs were employed including geometric, floral and figural designs appropriate for the urban market. One defining feature was the use of texts, a practice possibly originating in the previous century in the Rhineland area of Germany with texts added to salt-glazed stoneware. Metropolitan wares produced in Essex featured texts applied in block letters with pious aphorisms urging humility, charity or loyalty to the crown. Texts influenced by the Puritan government of the day were replaced with royalist messages after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. See David Gaimster, "Regional Decorative Traditions in English Post-Medieval Slipware," in your course text, pp 129-130.

Medieval Jugs found in SE England

16. Medieval jugs found in SE England, earthenware, thrown, slip decorated, late 12th-early 13th c. Left to right: early 13th-c. made/found in London; mid 13th-century decorated jug made in Kingston; 13th-c. jug made in Rouen, found in Oxfordshire; late 12th-c. incised tripod pitcher made in London. Kingston Jug Medieval, late 13th century, From Kingston, Surrey, England. This jug was found in the nineteenth century in an old chalk well in Cannon Street, near London Bridge, during construction work. It takes its name from the medieval kiln in Surrey where it was probably made. It is highly decorated in a style which imitates French pottery and clearly demonstrates the influence of French tastes on English tableware in the thirteenth century. The rich variety of coloured glazes is achieved by the addition of iron (for brown/red), copper (for green) and lead (for yellow). The diamond-shaped panels, containing rampant lions (or dragons) alternating with dark green inverted chevrons, show both the imagination and technical diversity of the medieval potter. Height: 28.5 cm (British Museum

Bernard Palissy Lead Glazed piece rustique

Deruta, Maiolica Dish

14. Italy, Deruta, Maiolica dish, c. 1490-1525 inscribed PÊDORMIRENONSAQUISTA ('nothing is gained by sleeping'). Dia. 40 cm Height 8 cm. (British Museum)When applied to maiolica, the term 'belle donne' (Italian 'beautiful women') usually refers to a category of dishes or plates bearing female heads and a scroll inscribed with a name or motto. They were produced in large numbers in several Italian pottery centres between around 1520 and 1550, for a wide variety of clients. The female image is idealized to such a degree that it is unlikely to be an accurate likeness of a particular woman. However, the names, either with or without adjective or mottoes, are thought to refer to contemporary women, often local worthies or local beauties, as suggested by a contemporary sonnet addressed to a potter in Todi, not far from Deruta. Those pieces with a moralizing inscription are not belle donne wares in the true sense, but are part of the artistic tradition of portraying female images with a moralizing statement, often one that appears to be specifically addressed to a female audience.

Delft Pyramid Vase

13.

Holland, Delft, Pyramid vase, tin-glaze earthenware, 1690-1720, over 100 cm high.

This form is called a tulip or pyramid vase. In fact, it was not only used for tulips; all sorts of cut flowers could be arranged in it. This example was made in Delft, between 1690 and 1720 and it is more than a metre high. The construction comprises a stack of vases. Inside, a wooden stick holds the successive basins in place. The separate vases were needed because all the flowers required their own water supply. To make the vase in one piece would have been counterproductive: the water would have escaped once it rose above the bottom spouts. But that was not the only reason why a stack of successive vases was chosen. In 1700 Delft potters had not yet discovered how to fire such high forms. As a single piece, this vase would have collapsed in the kiln. Vases with spouts for individual flowers were made in all sorts of shapes in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. The pyramid vase was the ultimate achievement in this field.

Forty flowers could be arranged in this tower of Delft blue Faience, a type of pottery covered in a thick white tin glaze. Usually the glaze is decorated with motifs before being fired in the kiln for the last time. This type of pottery - unlike porcelain - is not pure white: the inside inner layer is brown or beige. The word 'faience' comes from Faenza, on of the Italian cities that specialised in this type of pottery in the 14th and 15th centuries. Faience is also called majolica, presumably a corruption of Majorca. It was through this island that the pottery was shipped. In the 17th century Delft became a major centre of painted faience production. Delftware was renowned as a skilful imitation of Chinese porcelain. The vase is decorated with flowers and birds. On the base, Flora, the goddess of flowers, is painted. The form of the tower is based on two exotic structures which were in fashion in the late seventeenth century. The pointed shape is reminiscent of the Egyptian obelisk. An obelisk is a square-sectioned column tapering towards the top and culminating in a pyramid. The origins of the form lie in ancient Egypt. Numerous obelisks were taken by the Romans from Egypt and displayed throughout Rome as decorative monuments. In the Renaissance the obelisk returned in smaller form as an ornamental motif., a structure that symbolised immortality and princely fame. A pagoda is a freestanding tower-like Asiatic structure. The word is usually applied to Chinese temples built up of different levels. Miniature pagodas are often found in Western art as motifs intended to give an object an oriental tint. Pagodas were known in the Netherlands from illustrations in seventeenth-century travel descriptions of China. The mystery of far-off China caught people's imagination in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.The French word 'Chinoiserie' actually means a work of art from China. However, the term is usually employed to denote the fashion for oriental, or Chinese shapes that raged in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. The term 'chinoiserie' is also used for an object dating from this China fashion, such as the gardens with Chinese temples and pagodas or the imitation Chinese porcelain, with imitation Chinese decorations. Often, the decorative motifs comprised a mixture of fantasised Chinese or Oriental figures and shapes together with European Rococo ornamentation, decorated walls, furniture and dinnerware. (Rijksmuseum)

Holland, Delft, Pyramid vase, tin-glaze earthenware, 1690-1720, over 100 cm high.

This form is called a tulip or pyramid vase. In fact, it was not only used for tulips; all sorts of cut flowers could be arranged in it. This example was made in Delft, between 1690 and 1720 and it is more than a metre high. The construction comprises a stack of vases. Inside, a wooden stick holds the successive basins in place. The separate vases were needed because all the flowers required their own water supply. To make the vase in one piece would have been counterproductive: the water would have escaped once it rose above the bottom spouts. But that was not the only reason why a stack of successive vases was chosen. In 1700 Delft potters had not yet discovered how to fire such high forms. As a single piece, this vase would have collapsed in the kiln. Vases with spouts for individual flowers were made in all sorts of shapes in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. The pyramid vase was the ultimate achievement in this field.

Forty flowers could be arranged in this tower of Delft blue Faience, a type of pottery covered in a thick white tin glaze. Usually the glaze is decorated with motifs before being fired in the kiln for the last time. This type of pottery - unlike porcelain - is not pure white: the inside inner layer is brown or beige. The word 'faience' comes from Faenza, on of the Italian cities that specialised in this type of pottery in the 14th and 15th centuries. Faience is also called majolica, presumably a corruption of Majorca. It was through this island that the pottery was shipped. In the 17th century Delft became a major centre of painted faience production. Delftware was renowned as a skilful imitation of Chinese porcelain. The vase is decorated with flowers and birds. On the base, Flora, the goddess of flowers, is painted. The form of the tower is based on two exotic structures which were in fashion in the late seventeenth century. The pointed shape is reminiscent of the Egyptian obelisk. An obelisk is a square-sectioned column tapering towards the top and culminating in a pyramid. The origins of the form lie in ancient Egypt. Numerous obelisks were taken by the Romans from Egypt and displayed throughout Rome as decorative monuments. In the Renaissance the obelisk returned in smaller form as an ornamental motif., a structure that symbolised immortality and princely fame. A pagoda is a freestanding tower-like Asiatic structure. The word is usually applied to Chinese temples built up of different levels. Miniature pagodas are often found in Western art as motifs intended to give an object an oriental tint. Pagodas were known in the Netherlands from illustrations in seventeenth-century travel descriptions of China. The mystery of far-off China caught people's imagination in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.The French word 'Chinoiserie' actually means a work of art from China. However, the term is usually employed to denote the fashion for oriental, or Chinese shapes that raged in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. The term 'chinoiserie' is also used for an object dating from this China fashion, such as the gardens with Chinese temples and pagodas or the imitation Chinese porcelain, with imitation Chinese decorations. Often, the decorative motifs comprised a mixture of fantasised Chinese or Oriental figures and shapes together with European Rococo ornamentation, decorated walls, furniture and dinnerware. (Rijksmuseum)

Iran, Kashan, Stonepaste Bottle

12. Iran, Kashan, Stonepaste bottle, painted in lustre with seated figures and prowling animals Dated Muharram 575 AH, (CE 1179) Height: 14.3 cm.

The earliest known piece of Kashan lustreware. This bottle is the earliest known dated Iranian example of the lustreware technique. Its neck is missing, and the body is in a fragmentary state, but much of the decoration is clearly visible. The main band shows a seated group of people, against a background of leafy ornament which suggests a garden setting. Below the garden-party is an inscription of a poem. Below the inscription is a succession of hounds chasing hares, against a simple pattern of curling vegetation. This is a popular subject on luxury objects, referring to the favourite noble pastime of hunting. A similar band is on the top of the bottle. The lowest band is decorated with a trellis of stylized curling plant stems.Translation of poem on bottle:'Oh Heavenly sphere, why do you set afflictions before me? Oh Fortune, why do you scatter salt on my wounds? Oh Enemy of mine, how often will you strike at me? I am struck by my own fate and fortune.May joy, exultation and cheerfulness be with you.May prosperity, happiness and triumph be your companions.'(Translation: O. Watson)

The earliest known piece of Kashan lustreware. This bottle is the earliest known dated Iranian example of the lustreware technique. Its neck is missing, and the body is in a fragmentary state, but much of the decoration is clearly visible. The main band shows a seated group of people, against a background of leafy ornament which suggests a garden setting. Below the garden-party is an inscription of a poem. Below the inscription is a succession of hounds chasing hares, against a simple pattern of curling vegetation. This is a popular subject on luxury objects, referring to the favourite noble pastime of hunting. A similar band is on the top of the bottle. The lowest band is decorated with a trellis of stylized curling plant stems.Translation of poem on bottle:'Oh Heavenly sphere, why do you set afflictions before me? Oh Fortune, why do you scatter salt on my wounds? Oh Enemy of mine, how often will you strike at me? I am struck by my own fate and fortune.May joy, exultation and cheerfulness be with you.May prosperity, happiness and triumph be your companions.'(Translation: O. Watson)

Iraq, Abbasid Dynasty Bowl

11. Iraq, Abbasid dynasty, 9th c. Bowl. earthenware, painted in-glaze. 5.7 x 20.8 x 20.8 cm. (Freer Gallery)

Among the earliest surviving works of art decorated with writing are a group of ceramic vessels, produced in Iraq and Iran under the rule of the powerful Abbasid dynasty (749–1258). Inspired by the whiteness and purity of the much admired, imported Chinese porcelain, Muslim potters created their own "white ware" by covering their buff-colored earthenware vessels with a glaze containing a small amount of lead and tin, which turns opaque when fired. This bowl combines both vegetal motifs and calligraphic design in cobalt and copper glazes. Surrounded by windswept palmettes, the inscription in the center confers blessings to the owner. (Freer)

Among the earliest surviving works of art decorated with writing are a group of ceramic vessels, produced in Iraq and Iran under the rule of the powerful Abbasid dynasty (749–1258). Inspired by the whiteness and purity of the much admired, imported Chinese porcelain, Muslim potters created their own "white ware" by covering their buff-colored earthenware vessels with a glaze containing a small amount of lead and tin, which turns opaque when fired. This bowl combines both vegetal motifs and calligraphic design in cobalt and copper glazes. Surrounded by windswept palmettes, the inscription in the center confers blessings to the owner. (Freer)

Thailand, Si Satchanalai Covered Box

10. Thailand, Si Satchanalai, Ayutthaya period. 15-16th c. Covered Box with Interior Tray. Stoneware with iron glaze and iron pigment under clear glaze. W. 8 cm. (Freer Gallery)

Painted decoration on Mainland Southeast Asian ceramics related to indigenous traditions of painting (and writing), such as murals or illustrated manuscripts on palm leaf or paper. An intriguing aspect of painted ceramic decoration is the nature of the brush employed. Some forms of decoration on Sawankhalok and Sukhothai ceramics appear to be executed with a stiff brush (possibly softened plant fiber) that leaves crisp, blunted ends to the lines. Elsewhere, in Kalong or at the Red River Delta kilns in North Vietnam, the soft, flexible Chinese-style animal-hair brush must have been employed, judging from the quality of line and outline.

Painted iron decoration covered by clear glaze (or possibly applied over it) appeared on stoneware made at the Dai La kiln site west of Hanoi in the fourteenth century. Some dishes and bowls made at the Binh Dinh (Vijaya) kilns in Central Vietnam also bore iron decoration under the glaze. Similar underglaze decoration on stoneware was produced at the Sawankhalok kilns on MON-associated stoneware (MASW). This production occurred in the early decades of the fifteenth century, according to shipwreck evidence.

Around the same time, the Sukhothai kilns produced wares with iron decoration over thick white slip, which became their standard mode, while the Sawankhalok kilns shifted by mid-fourteenth century to a focus on celadon glaze. It is possible that the use of iron-painted decoration in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries represented a response to iron-decorated wares imported from southern Chinese kilns, such as the Haikang kilns in southern Guangdong province. By contrast, a later (sixteenth-century) phase of iron decoration at Sawankhalok and Kalong appears to be an attempt to replicate (in the absence of the actual blue pigment) the decoration executed with cobalt on wares from North Vietnam and southern China. Similar iron decoration appears on very few ceramics from Lower Burma dating to the sixteenth century (Freer Gallery).

Note: The term 'Sawankhalok' was used at one stage to describe all ceramics made at Si-Satchanalai in north-central Thailand. By the mid 14th century, the rising kingdom of Ayudhya used the name Sawankhalok ('place of heaven') to describe the ancient town of Si-Satchanalai, which had a long ceramic tradition. However, the modern town and province of Sawankhalok were never associated with ceramics, so to avoid confusion the name Si-Satchanalai should be used to describe the ceramics made in that area. (Maritime Asia)

Vietnamese Bowl with Underglaze Blue

9. Vietnam, 15th c. Bowl. Stoneware painted with underglaze cobalt blue. H. 6.7; D. 24.4 cm.

Although the peony in the interior of this bowl is a Chinese motif, its placement as the central medallion is distinctly Vietnamese; peonies on Chinese ceramics are more likely to occupy the horizontal register on vases. The base of the bowl is covered with a chocolate-brown mixture of clay and water, or slip. The covering of the bottom of a ceramic piece in this fashion is found on wares from Vietnam and Thailand, but has no technical explanation and the purpose of this slip remains unclear. The choice may have reflected aesthetic preferences, or it may have served a more practical function. For example, the brown base may have served to differentiate vessels used in religious or other types of ceremonies from those used in more mundane settings or it may have been a potter's mark or possibly a counting symbol of some sort (Asia Society).

Production of glazed ceramics began in Vietnam about two thousand years ago. The making of blue and white (cobalt) stoneware was spurred on by the Ming-period invasion and annexation of Vietnam from 1407 to 1428 and the imperial Chinese prohibition of the ceramic trade from 1436 to 1465. Originally used in Vietnam to replace the black underglaze iron decoration common on ceramics made during the 13th and 14th centuries, underglaze cobalt blue quickly became the most common color for painting Vietnamese ceramics.

Although the Chinese annexation of Vietnam may have provided the technology for blue-and-white wares, economic competition was an important stimulus in their development. By the 15th century, blue-and-white wares were the most popular ceramics in the world. Active markets for them existed in East Asia, throughout Southeast Asia, and in the Middle East. The Chinese prohibition of exporting ceramics for almost thirty years during this time of high demand provided an ideal opportunity for the Vietnamese ceramic industry to expand, and the Vietnamese reliance on Chinese prototypes was most likely a deliberate attempt to capitalize on the contemporary desire for Chinese-style wares (Freer Gallery notes).

Koryo Dynasty Buddhist Kundika

8. Korea, Koryo period, late 12-early 13th c. Buddhist ritual sprinkler (kundika). Stoneware with white slip inlay under celadon glaze. H. 35.8 W 14.4 D 13.0 cm.

This vessel, used for sprinkling sacred water during Buddhist ceremonies, illustrates the effectiveness of inlay for pictorial decoration on ceramics. Black and white inlays within incised motifs (sanggam technique) portray a tranquil scene in which a willow tree stands alongside a lotus pond. Similar landscapes appear on bronze ritual sprinklers inlaid with silver wire. This piece was made at the Puan kiln complex in southwestern Korea.

Many celadons were produced for Buddhist rituals—the shapes are based on metal originals. The Kundika—water sprinkler, a shape originally from India—traveled along silk route to China and Korea. Bowl sets for hand washing, incense burners, many in animal shapes were also produced for Buddhist monasteries. The wares travelled by boat from kilns in the south-west to the capital at Songdo, modern day Kaesong. Recent excavations of shipwrecks in area show volume of celadon production.

The technique known as sanggam developed in the second half 12th c.Carved, incised decoration is inlaid with another colour of slip. The technique derives from metal and lacquer ware—inlaying gold, silver into bronze, mother-of-pearl into lacquer. Designs of clouds, flowers, grapes etc. were carved into leather-hard forms. They were then painted with the inlay material, allowed to harden, and then the excess was scraped off excess to reveal design. The works were then glazed and fired. The inlay not strictly clay; it consisted of crushed quartz for white and iron-rich material for black.

Momoyama Period Ewer for Tea Ceremony

7. Japan, Momoyama period (1568–1615), early 17th century. Ewer for Use in Tea Ceremony, Shino-Oribe ware with iron decoration.

This beautiful ewer was made as a wine server for the "kaiseki," or the meal that precedes the tea ceremony. With its bold contour and charmingly painted floral and textile patterns, it is one of the most attractive and rare examples of a type of ware known as Shino-Oribe. The body of refined clay is covered with a white feldspathic glaze that fired a purplish pink where it pooled and interacted with the iron. Shino ware, the first decorated white ware in Japan, was developed in the sixteenth century in Mino, Gifu Prefecture. This piece is a fascinating example of the transformation of Mino ceramics in accordance with the taste of the tea master Furuta Oribe (1544–1615) and the technical changes brought about by the introduction, in the early seventeenth century, of a more advanced kiln type, the chambered climbing kiln modeled on those built by Korean craftsmen at Karatsu in Kyushu. The earliest and most important new kiln was the one at Motoyashiki, in Mino, where utensils for the tea masters of Kyoto were produced to order. At Motoyashiki the green-glazed decorated wares known as Oribe ware were produced, but excavations reveal that Shino wares continued to be made there in the early period. Inevitably prevailing taste and new technology brought forth the changes in Shino ware that are reflected in the more refined form and inventive decoration of this vessel

This beautiful ewer was made as a wine server for the "kaiseki," or the meal that precedes the tea ceremony. With its bold contour and charmingly painted floral and textile patterns, it is one of the most attractive and rare examples of a type of ware known as Shino-Oribe. The body of refined clay is covered with a white feldspathic glaze that fired a purplish pink where it pooled and interacted with the iron. Shino ware, the first decorated white ware in Japan, was developed in the sixteenth century in Mino, Gifu Prefecture. This piece is a fascinating example of the transformation of Mino ceramics in accordance with the taste of the tea master Furuta Oribe (1544–1615) and the technical changes brought about by the introduction, in the early seventeenth century, of a more advanced kiln type, the chambered climbing kiln modeled on those built by Korean craftsmen at Karatsu in Kyushu. The earliest and most important new kiln was the one at Motoyashiki, in Mino, where utensils for the tea masters of Kyoto were produced to order. At Motoyashiki the green-glazed decorated wares known as Oribe ware were produced, but excavations reveal that Shino wares continued to be made there in the early period. Inevitably prevailing taste and new technology brought forth the changes in Shino ware that are reflected in the more refined form and inventive decoration of this vessel

Muromachi Period Shigaraki Ware

6. Shigaraki was one of the ancient centres of pottery producing domestic wares, in the area which now forms Shiga Prefecture. Robust, thick-walled Shigaraki ware has been made since the Kamakura period (1185-1333). It is made with a sandy clay containing feldspar which is distinctly visible through the ash glaze. This jar is typical of the ware, with characteristic incised circles around the shoulder. Height: 33 cm (British Museum).

Ming Dynasty Export "Kraak" Ware

5. China, Ming Dynasty, early 17th c., porcelain, export market, “kraak” ware, Porcelain with cobalt blue underglaze. 28.6 cm

A defining feature of kraak porcelain (so-called from the Dutch name for caracca, the Portuguese merchant ship) is the device of paneled decoration, seen here in the wide border of the dish, with its alternation of sunflowers and emblems. The central scene of ducks on a pond and the paneled motifs are among the numerous variants on the basic format of this extensive class of export porcelain. Examples similar to the Museum's dish, which is well made and painted with strong color and with care, if not with spirit, were found in the cargo of the Dutch ship Witte Leeuw, sunk in battle off Saint Helena in 1613.

A defining feature of kraak porcelain (so-called from the Dutch name for caracca, the Portuguese merchant ship) is the device of paneled decoration, seen here in the wide border of the dish, with its alternation of sunflowers and emblems. The central scene of ducks on a pond and the paneled motifs are among the numerous variants on the basic format of this extensive class of export porcelain. Examples similar to the Museum's dish, which is well made and painted with strong color and with care, if not with spirit, were found in the cargo of the Dutch ship Witte Leeuw, sunk in battle off Saint Helena in 1613.

Yuan Dynasty, "David Vases"

4. China, Yuan Dynasty. Pair of temple vases, inscribed 1351. Porcelain with cobalt blue underglaze. Height: 63.5 cm.

"David Vases" 1351. With high hollow foot & elephant handles, decorated in brilliant blue. The decoration is distributed in a series of bands, the main field round the body bearing a vigorous 4 clawed dragon pursuing a pearl through clouds, with a wave pattern below. Round the foot is a peony scroll above a band of small panels containing auspicious symbols. Above the main field, on the shoulder, is a formal scroll; the lower part of the neck is decorated with phoenix among clouds, & the upper part with plantain leaves, interrupted on one side to make space for an inscription. Round the mouth is a floral scroll. The glaze is blue tinged. Height: 63.5

"David Vases" 1351. With high hollow foot & elephant handles, decorated in brilliant blue. The decoration is distributed in a series of bands, the main field round the body bearing a vigorous 4 clawed dragon pursuing a pearl through clouds, with a wave pattern below. Round the foot is a peony scroll above a band of small panels containing auspicious symbols. Above the main field, on the shoulder, is a formal scroll; the lower part of the neck is decorated with phoenix among clouds, & the upper part with plantain leaves, interrupted on one side to make space for an inscription. Round the mouth is a floral scroll. The glaze is blue tinged. Height: 63.5

Northern Song Cizhou Vase

3. Northern Song, Cizhou vase, late 11th – early 12th c., stoneware with carved slip decoration, 29 cm.

Cizhou (or tzu-chou) wares from Hopei (or Hebei) province are the largest group of stonewares—light grey clay body covered with white slip and vigorous free—hand painted floral, foliage designs—sometimes scratched through dark slip to white, meanders, peony, diaper patterns. Sometimes overglaze red, green added. Used for everyday wares—pillows, brush pots, wine jars, bowls, boxes, vases.

Cizhou (or tzu-chou) wares from Hopei (or Hebei) province are the largest group of stonewares—light grey clay body covered with white slip and vigorous free—hand painted floral, foliage designs—sometimes scratched through dark slip to white, meanders, peony, diaper patterns. Sometimes overglaze red, green added. Used for everyday wares—pillows, brush pots, wine jars, bowls, boxes, vases.

Song Dynasty Ding Ware Bowl

2. China, Hebei province, Northern Song Dynasty, late 11th-early 12th c. CE. Ding Ware Bowl, Porcelain with moulded decoration, bound in copper, Diameter: 21.3 cm (at mouth), 4.2 cm (at foot)

This bowl was produced at the Ding kilns in Hebei province, northern China, whose white porcelains were considered one of the 'five great wares' of the Song Dynasty (AD 960-1279 AD). The others were called Ru, Jun, Guan and Ge wares. Ding wares were sent to the Imperial court as tribute as early as AD 980.Early Ding wares were fired in separate saggars, with each piece having been incised individually. In the late eleventh or early twelfth century, they began using moulds for decoration and stacked the pieces for firing, which allowed mass production. The decorative effect differs greatly between the early and the later examples.The decoration on this bowl is a good example of the later, moulded type. Children play among lotus flowers, a common motif in Chinese ceramics, paintings and textiles. The moulds became less crisp with repeated use, but this appears to be one of the first impressions, as the decoration is still very clear.The metal band around the mouth is made of a copper alloy. Apart from its decorative use, it also smoothed the rough, unglazed rim.Diameter: 21.3 cm (at mouth) Diameter: 4.2 cm (at foot)

This bowl was produced at the Ding kilns in Hebei province, northern China, whose white porcelains were considered one of the 'five great wares' of the Song Dynasty (AD 960-1279 AD). The others were called Ru, Jun, Guan and Ge wares. Ding wares were sent to the Imperial court as tribute as early as AD 980.Early Ding wares were fired in separate saggars, with each piece having been incised individually. In the late eleventh or early twelfth century, they began using moulds for decoration and stacked the pieces for firing, which allowed mass production. The decorative effect differs greatly between the early and the later examples.The decoration on this bowl is a good example of the later, moulded type. Children play among lotus flowers, a common motif in Chinese ceramics, paintings and textiles. The moulds became less crisp with repeated use, but this appears to be one of the first impressions, as the decoration is still very clear.The metal band around the mouth is made of a copper alloy. Apart from its decorative use, it also smoothed the rough, unglazed rim.Diameter: 21.3 cm (at mouth) Diameter: 4.2 cm (at foot)

Tang Figure of Seated Woman

1. China, Tang Dynasty. Figure of a seated woman holding a bird, first half of 8th century earthenware with sancai (three-color) lead-silicate glaze H: 40.6 W: 17.9 D: 15.6 cm

This sensitively observed figure of a court woman offers insights into the cosmopolitan, wealthy lifestyle of the Tang dynasty (618–907) elite in the first half of the eighth century. Made as a burial good, this sculpture reflects competition among the Tang aristocracy to display numerous expensively crafted earthenware figures in funerary processions—grander objects indicated higher family status.Early eighth-century potters achieved a high point by imbuing ceramic figures with considerable naturalism and fidelity, despite using molds. Here, the double topknot and tie-dyed pattern on the woman's jacket realistically illustrate Tang fashion. The songbird she gazes upon alludes to Tang fascination with birds imported from India and the tropics.

This sensitively observed figure of a court woman offers insights into the cosmopolitan, wealthy lifestyle of the Tang dynasty (618–907) elite in the first half of the eighth century. Made as a burial good, this sculpture reflects competition among the Tang aristocracy to display numerous expensively crafted earthenware figures in funerary processions—grander objects indicated higher family status.Early eighth-century potters achieved a high point by imbuing ceramic figures with considerable naturalism and fidelity, despite using molds. Here, the double topknot and tie-dyed pattern on the woman's jacket realistically illustrate Tang fashion. The songbird she gazes upon alludes to Tang fascination with birds imported from India and the tropics.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

Technical considerations

Porcelain--note platey structure. Figure 1a (should be below)

Porcelain--note platey structure. Figure 1a (should be below) Updraft kiln, firebox separate Figure 7c

Updraft kiln, firebox separate Figure 7c Chinese Dragon Kiln Figure 7b

Chinese Dragon Kiln Figure 7b Bonfire/Neolithic kilns Figure 7a

Bonfire/Neolithic kilns Figure 7a Tin glaze Figure 6

Tin glaze Figure 6 German Salt Glaze Figure 5

German Salt Glaze Figure 5 Roman sigillata body and slip Figure 4

Roman sigillata body and slip Figure 4 Faience Figure 3

Faience Figure 3 Vegetable temper (above) and Roman smooth body (below)

Vegetable temper (above) and Roman smooth body (below)Figure 2

Calcareous clay (above)/Limey earthenware Figure 1b/c (note: porcelain image at top)

Calcareous clay (above)/Limey earthenware Figure 1b/c (note: porcelain image at top)Hello Class, Here are the technical notes I showed you in class. Remember, they are very basic!

Technical Considerations

• Clay: A fine-grained natural material which, when wet, is characterized by its plasticity, the property which allows it to be deformed by pressure into a desired shape without cracking and to keep this shape when the pressure is removed. In addition to clay minerals, clay typically contains feldspar, calcite and iron oxide.

• Clay Minerals: A group of very fine-grained minerals (alumino silicates) which are the main constituents of clay. They occur as minute platelets which, when wet, slide across one another, giving the clay its plastic properties.

Clay Structure (Ceramic Masterpieces) fig1.8 p38 particles of Kaolinite. Fine platelets occur as stacks that require intensive mixing to break up into individual particles. When separated by water films, the platelets slide over one another to give good plasticity to a clay-water paste. (above figure 1a)

figure 13.2 p. 235 Calcereous illite clay from Corinth consists of much finer platey particles and has high impurity content (potassia, calcia, iron, titania); Limey earthenware clay from Iran more impure, finer particle, less-well developed platey nature. (figures 1b/c)

• Clay: A fine-grained natural material which, when wet, is characterized by its plasticity, the property which allows it to be deformed by pressure into a desired shape without cracking and to keep this shape when the pressure is removed. In addition to clay minerals, clay typically contains feldspar, calcite and iron oxide.

• Clay Minerals: A group of very fine-grained minerals (alumino silicates) which are the main constituents of clay. They occur as minute platelets which, when wet, slide across one another, giving the clay its plastic properties.

Clay Structure (Ceramic Masterpieces) fig1.8 p38 particles of Kaolinite. Fine platelets occur as stacks that require intensive mixing to break up into individual particles. When separated by water films, the platelets slide over one another to give good plasticity to a clay-water paste. (above figure 1a)

figure 13.2 p. 235 Calcereous illite clay from Corinth consists of much finer platey particles and has high impurity content (potassia, calcia, iron, titania); Limey earthenware clay from Iran more impure, finer particle, less-well developed platey nature. (figures 1b/c)

Primary and Secondary Clays

Clay occurs naturally in beds of weathered and decomposed granite and gneiss that makes up 85% of the earth’s surface.

Primary clays are found on the site of the parent feldspathic rock and are relatively pure, containing only materials that were part of the parent rock such as feldspar, quartz and mica. They are typically white, large grained and aplastic with low shrinkage. They have a high melting point and require flux to decrease firing temperature (i.e. kaolin).

Secondary clays are deposited away from the parent rock by water or wind and are characterized by fine, uniform particles. They tend to be very plastic and require the addition of other materials such as sand or grog to prevent excessive shrinkage.

• Calcareous Clay: contains more than 5% lime, usually in the form of calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO), the main constituent of limestone. Clays of this type are typically alluvial and were widely used in the Mediterranean and the Near East. Calcareous clays fire to a very stable structure in the range of 850-1050 degrees C, characteristic of much ancient pottery. Careful control of temperature was not necessary and a wide range of colours would result from a single firing.

• Potters clean and refine their dug clay by levigation--washing clay in slurry form, allowing it to settle and pouring off liquid with finer particles in suspension into additional tubs. It is generally aged and foreign particles are removed. Often sand, crushed pots, shell or other materials are added to improve the clay body, to give it bulk, strength, ability to withstand rapid changes in heat etc. Washed clay needs to be wedged (pugged) to eliminate air bubbles and foreign materials. In factory situations, specialized workers look after each of these tasks.

Temper in Pots

Micrographs showing vegetable temper (top) and numerous grains of very fine sand or silt in romanised ware (bottom). Note the regular, well-sorted size distribution of particles. The inclusion of temper improves thermal shock resistance in bonfire firing and cooking. Hand-pots break less-easily than do wheel-thrown wares. (PMCT p.58) (Figure 2 above)

Forming techniques:

Methods are direct (throwing, hand forming, carving, turning, modelling) or indirect (moulding). Clay can be squeezed, pinched and paddled into shape. Pinch or thumb pots most familiar--limit to size, but otherwise, any level of sophistication possible. Pinching and hand forming can also be done to embellish a thrown pot--ie, additional ornaments, lip or foot design. Hand-building can involve cutting slabs of clay to patterns and luting edges together. Coil building can simulate wheel-throwing in roundness, uniformity. Often walls thinned and raised by beating with paddle, supporting wall from inside of pot with “anvil.” Huge pots made in this way still in Greece, Asia. Finished pots may be burnished with stone, shell or mineral like hematite to align particles/consolidate surface and gives degree of impermeability and beautiful sheen.

Molding technique originated with bronze casting, carried over to ceramics. Single valve (i.e. sprig molds) designs fairly flat but can later be undercut. Efficient way to produce identical or nearly-identical multiples--sometimes hand finishing makes each one subtly different. Romans industrialize ceramics through molds. Double-valve molds--two sides to mold fit together, side seams smoothed over--enable replication of eccentric shapes that otherwise would require very slow building techniques. Slip casting more efficient--wet slip poured into mold, sloshed around, excess poured off (can be repeated)--shrinkage makes clay pull away. Cutting: can elaborate surface by piercing, cutting patterns into it. Might also involve impressing various tools, seals; inlaid patterns can later be filled in with contrasting coloured slip (Korean celadons from 10-14th c.) or as intensification of glaze (Sung-Dynasty).

Potter’s Wheel

consists of top circular bat, bearing or bearings, on which wheel rotates, heavy flywheel that can be turned by assistant or by foot and which will turn for a long time, leaving hands free to work. Very tall pots usually thrown in sections and joined--wet clay will only support so much weight for thickness of walls. Accurate throwing might involve templates, pointers for measuring. Clay can be thrown into concave molds fixed to bat--useful for mass-production of identical items, especially bowls with relief-molded decoration. Jiggering--mold fixed to bat, template made for external radius--mold is usually convex--place pancake or bat of clay over mold, lower arm over spinning clay--press until excess is shaved away. Turning: shaving-down of green-hard pot to thin walls--refines shape--Chinese eggshell porcelains (18th c) shaved to almost unbelievable thinness. Used to perfect profiles of shoulders, rims, feet, flanges etc.

Slips and Glazes:

make pots impervious (for earthenware) or stronger, more chip-resistant and enhance appearance. Slips are clay particles suspended in water, often have materials added to enhance suspension and/or colouring agents. Slips have natural affinity for clay body. Glazes have additional fluxes added and consist mainly of colouring agent--metal or metalic oxide, with glassy agent--silica (quartz, flint or sand) plus flux (lead, soda, wood-ash, borax or magnesia) to lower melt temperature of silica plus frit, clay, feldspar etc. to give “body” to glaze. Raw glazes--naturally insoluble with limestone and feldspar as main fluxes or lead glazes and fritted glazes in which soluble alkalis are rendered insoluble by fritting--melting with silica and later milled and sifted for uniform particle size.

Fritting renders toxic ingredients like heavy metals, lead non-toxic. Soluble alkalis are problematic because the effloresce on the surface during drying and result in non-uniform composition with poor surface qualities.

Glaze materials fire different colours under different conditions. Main difference created by oxidizing--clear, bright flame, lots of oxygen--colouring agents remain in oxide form versus reduction--smoky, choked flame, “robs” oxygen from glaze or body of pot (oxygen combines with excess carbon in atmosphere), creates different colours--coloring agents are the metals themselves, not in oxide form. Alternations in environment can cause interesting speckles, different pots in same batch to fire differently, and are essential to Greek red and black pots.

Salt-glaze and Wood Ash--unique--enhance characteristic of clay itself--used on stoneware. Salt (NaCl) thrown into kiln over 1100 degrees C. decomposes, releasing chlorine gas. Silica acts as powerful flux on surface of pots--fuses ahead of rest of body, causing shiny glassy surface, often speckled. Very popular in Germany late middle-ages. Wood ashes dusted on pots prior to being put into kiln or exposed to ash from fire in kiln--effect is rustic, “natural”, highly-sought after in Japan.

Micrographs showing vegetable temper (top) and numerous grains of very fine sand or silt in romanised ware (bottom). Note the regular, well-sorted size distribution of particles. The inclusion of temper improves thermal shock resistance in bonfire firing and cooking. Hand-pots break less-easily than do wheel-thrown wares. (PMCT p.58) (Figure 2 above)

Forming techniques:

Methods are direct (throwing, hand forming, carving, turning, modelling) or indirect (moulding). Clay can be squeezed, pinched and paddled into shape. Pinch or thumb pots most familiar--limit to size, but otherwise, any level of sophistication possible. Pinching and hand forming can also be done to embellish a thrown pot--ie, additional ornaments, lip or foot design. Hand-building can involve cutting slabs of clay to patterns and luting edges together. Coil building can simulate wheel-throwing in roundness, uniformity. Often walls thinned and raised by beating with paddle, supporting wall from inside of pot with “anvil.” Huge pots made in this way still in Greece, Asia. Finished pots may be burnished with stone, shell or mineral like hematite to align particles/consolidate surface and gives degree of impermeability and beautiful sheen.

Molding technique originated with bronze casting, carried over to ceramics. Single valve (i.e. sprig molds) designs fairly flat but can later be undercut. Efficient way to produce identical or nearly-identical multiples--sometimes hand finishing makes each one subtly different. Romans industrialize ceramics through molds. Double-valve molds--two sides to mold fit together, side seams smoothed over--enable replication of eccentric shapes that otherwise would require very slow building techniques. Slip casting more efficient--wet slip poured into mold, sloshed around, excess poured off (can be repeated)--shrinkage makes clay pull away. Cutting: can elaborate surface by piercing, cutting patterns into it. Might also involve impressing various tools, seals; inlaid patterns can later be filled in with contrasting coloured slip (Korean celadons from 10-14th c.) or as intensification of glaze (Sung-Dynasty).

Potter’s Wheel

consists of top circular bat, bearing or bearings, on which wheel rotates, heavy flywheel that can be turned by assistant or by foot and which will turn for a long time, leaving hands free to work. Very tall pots usually thrown in sections and joined--wet clay will only support so much weight for thickness of walls. Accurate throwing might involve templates, pointers for measuring. Clay can be thrown into concave molds fixed to bat--useful for mass-production of identical items, especially bowls with relief-molded decoration. Jiggering--mold fixed to bat, template made for external radius--mold is usually convex--place pancake or bat of clay over mold, lower arm over spinning clay--press until excess is shaved away. Turning: shaving-down of green-hard pot to thin walls--refines shape--Chinese eggshell porcelains (18th c) shaved to almost unbelievable thinness. Used to perfect profiles of shoulders, rims, feet, flanges etc.

Slips and Glazes:

make pots impervious (for earthenware) or stronger, more chip-resistant and enhance appearance. Slips are clay particles suspended in water, often have materials added to enhance suspension and/or colouring agents. Slips have natural affinity for clay body. Glazes have additional fluxes added and consist mainly of colouring agent--metal or metalic oxide, with glassy agent--silica (quartz, flint or sand) plus flux (lead, soda, wood-ash, borax or magnesia) to lower melt temperature of silica plus frit, clay, feldspar etc. to give “body” to glaze. Raw glazes--naturally insoluble with limestone and feldspar as main fluxes or lead glazes and fritted glazes in which soluble alkalis are rendered insoluble by fritting--melting with silica and later milled and sifted for uniform particle size.

Fritting renders toxic ingredients like heavy metals, lead non-toxic. Soluble alkalis are problematic because the effloresce on the surface during drying and result in non-uniform composition with poor surface qualities.

Glaze materials fire different colours under different conditions. Main difference created by oxidizing--clear, bright flame, lots of oxygen--colouring agents remain in oxide form versus reduction--smoky, choked flame, “robs” oxygen from glaze or body of pot (oxygen combines with excess carbon in atmosphere), creates different colours--coloring agents are the metals themselves, not in oxide form. Alternations in environment can cause interesting speckles, different pots in same batch to fire differently, and are essential to Greek red and black pots.

Salt-glaze and Wood Ash--unique--enhance characteristic of clay itself--used on stoneware. Salt (NaCl) thrown into kiln over 1100 degrees C. decomposes, releasing chlorine gas. Silica acts as powerful flux on surface of pots--fuses ahead of rest of body, causing shiny glassy surface, often speckled. Very popular in Germany late middle-ages. Wood ashes dusted on pots prior to being put into kiln or exposed to ash from fire in kiln--effect is rustic, “natural”, highly-sought after in Japan.

Transfer printing important industrial technique--first used in Liverpool or Worchester for soft-paste porcelain in 1756. Makes use of copper plate engraving technology --copper plate is engraved--pigment applied to roller, plate wiped clean (pigment remains in grooves)--plate is printed onto thin paper attached to wares. Ware is then glazed and fired. Alternate process uses gelatin bat to deposit oil onto glazed wares, which are dusted with overglaze pigments and low-fired.

Faience (Figure 3)

Faience: Analysis of Egyptian faience reveals there is no deliberately added clay. The body was composed of crushed quartz, as shown in the micrograph, with small amounts of glass that bound the quartz grains together. A continuous glassy layer covers the surface. The body is porous, with holes showing as black. The glaze improves appearance and stabilizes surface/faience object. (PMCT p.104.)

Faience (Figure 3)

Faience: Analysis of Egyptian faience reveals there is no deliberately added clay. The body was composed of crushed quartz, as shown in the micrograph, with small amounts of glass that bound the quartz grains together. A continuous glassy layer covers the surface. The body is porous, with holes showing as black. The glaze improves appearance and stabilizes surface/faience object. (PMCT p.104.)

Roman Terra Sigillata Bodies and Slips (figure 4)

Roman factories were able to impose standardization through the use of fine, calcareous clays that fired to a consistent quality over a range of temperatures ranging from 850-1050 degrees common to wood fired updraft kiln. Glossy surface is achieved by use of a very fine slip oxidized to sealing-wax red. Micrograph of sherd of Eastern Gaulish sigillata shows open, partially-vitrified body and vitreous slip. The two adhere well with the resulting tough “non-stick” surface that made this ware popular for the table. (PMCT p.191)

Salt-Glazing (figure 5)